Bernard Elias - 10/26/2005

by Danny Bernstein

When I moved to WNC, the first book I read about the area was Strangers in High Places by Michael Frome. Among the many pictures sprinkled throughout the book was familiar face; it was Bernard Elias.

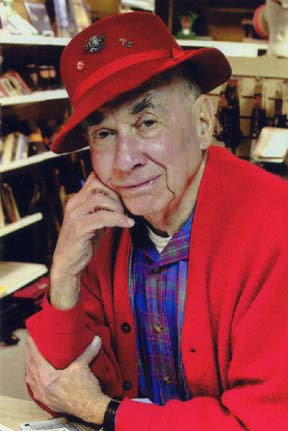

Almost 87 years old, Bernard Elias is the oldest member and has the longest tenure in the Carolina Mountain Club. Bernard, an

Wearing his red Swiss guide hat, Bernard explains his initial fascination with the mountains. He recalled that in 1929, the Asheville Times (precursor of the A-C-T) organized a ten-day expedition in the Smokies. And at that time, it was an expedition. The explorers took ten homing pigeons with them in the woods to deliver the news of their progress. Each day, they wrote up what they had done, put the report in a tiny aluminum capsule tied to the pigeon’s leg and sent the bird back to

“I was 10 at the time. I couldn’t wait for the paper to be delivered. That’s how I got so interested in the Smokies.”

The Smoky Mountains Hiking Club had a similar expedition from

Bernard grew up in

Bernard stayed in the scouts, became an Eagle Scout and that led to joining CMC in 1941; Arch Nichols was president. In those days, women were sometimes barred from exploratory trips.

“We wanted to explore a section of Linville Gorge but we were all unfamiliar with that area. Then it was considered the wildest area in

During WWII, Bernard was a navy photographer and that led to a career with Kodak, first in

“At the time,” Bernard recalls, “movie theaters in

His greatest contributions to the hiking community

Bernard considers the 100 Favorite Trails of the Great Smokies and

The map spans from

“You could scan the map without having to read five or six pages in a trail guide for each hike.” Both the National Park Service and National Geographic used the map as a reference. The map sold for a dollar. Now, 12 years after its last publication, those lucky enough to still have one have been offered upwards of $300 for it. Several of the hikes are now on private land, where hikers have to negotiate permission including

His second major contribution was more recent. Bernard was a good friend of Bill Kirkman, an early member of CMC. When Kirkman died, his estate, including thousands of slides, went to his niece.

“Bill was very meticulous and labeled all his slides,” Bernard said. Bill’s niece was at a loss of what to do with all these photos but recognized the value of the collection. She called Bernard. With Pete Steurer, the club historian, Bernard negotiated with the Special Collections librarian at UNCA, Helen Wykle, to create and house CMC material at the Ramsey Library. This collection now incorporates copies of Let’s Go, council minutes, as well as Kirkman’s 3,000 slides.

After a career that took him all over the world, Bernard came back to

Gerry McNabb remembers that he first met Bernard shortly after joining the club in 1964.

“I then knew him later when I was a customer at Ball Photo. I was very interested in photography, and soon discovered he was extremely knowledgeable about it. He has been a friend for a long time now. Bernard is extremely thorough in all he does and totally dedicated to the causes he is passionate about. He has a memory that could be the envy of a teenager. Bernard is unique.”

Conservation

Bernard explained that the CMC was historically very involved in conservation issues. One of the club’s biggest successes was the Wilderness designation for Shining Rock in 1964. Arch Nichols and Nina Forbes, along with the Georgia ATC, took the lead on that issue.

Bernard and other long-time members also give Arch Nichols credit for saving Max Patch. Max Patch was private land until 1982. One of its owners, Max, grew potatoes and turnips, hence the name, Max Patch. Max also grazed a flock of sheep up there. A developer bought the land and wanted to make it a resort area. That upset many people including Arch Nichols. According to Bernard, since Nichols worked for the Forest Service, he knew the ins and outs of that system. So Nichols convinced the Forest Service to buy the 392 acres for the

“It’s great that we saved Max Patch. Funnily enough,” Bernard recalls, “it was not that difficult to convince the owner to sell to the Forest Service. Maybe the developer realized that it was so remote he would not get too many customers, as was the case on nearby Camp Creek Bald.”

Bernard and many CMC members were very active in opposing the

“We organized CMC members to go to meetings and write letters opposing the road. We worked as hard on that as people are working now against the

Bernard is not leaving the